Horseradish (Armoracia rusticana, syn. Cochlearia armoracia) is a perennial plant of the family Brassicaceae (which also includes mustard, wasabi, broccoli, cabbage, and radish). It is a root vegetable, cultivated and used worldwide as a spice and as a condiment. The species is probably native to Southeastern Europe and Western Asia.

Description

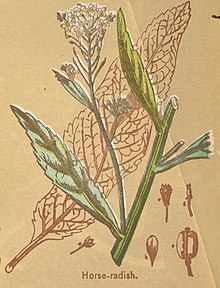

Horseradish grows up to 1.5 meters (5 feet) tall, with hairless bright green unlobed leaves up to 1 m (3 ft 3 in) long that may be mistaken for docks (Rumex).[3]: 423 It is cultivated primarily for its large, white, tapered root.[4][5][6][7] The white four-petalled flowers are scented and are borne in dense panicles.[3] Established plants may form extensive patches[3] and may become invasive unless carefully managed.[8]

Intact horseradish root has little aroma. When cut or grated, enzymes from within the plant cells digest sinigrin (a glucosinolate) to produce allyl isothiocyanate (mustard oil), which irritates the mucous membranes of the sinuses and eyes. Once exposed to air or heat, horseradish loses its pungency, darkens in color, and develops a bitter flavor.

History

Horseradish has been cultivated since antiquity. Dioscorides listed horseradish equally as Persicon sinapi (Diosc. 2.186) or Sinapi persicum (Diosc. 2.168),[9] which Pliny's Natural History reported as Persicon napy;[10] Cato discusses the plant in his treatises on agriculture. A mural in Ostia Antica shows the plant. Horseradish is probably the plant mentioned by Pliny the Elder in his Natural History under the name of Amoracia, and recommended by him for its medicinal qualities, and possibly the wild radish, or raphanos agrios of the Greeks. The early Renaissance herbalists Pietro Andrea Mattioli and John Gerard showed it under Raphanus.[11] Its modern Linnaean genus Armoracia was first applied to it by Heinrich Bernhard Ruppius, in his Flora Jenensis, 1745, but Linnaeus himself called it Cochlearia armoracia.

Both roots and leaves were used as a traditional medicine during the Middle Ages. The root was used as a condiment on meats in Germany, Scandinavia, and Britain. It was introduced to North America during European colonization; both George Washington and Thomas Jefferson mention horseradish in garden accounts.[12] Native Americans used it to stimulate the glands, stave off scurvy, and as a diaphoretic treatment for the common cold.[13]

William Turner mentions horseradish as Red Cole in his "Herbal" (1551–1568), but not as a condiment. In The Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes (1597), John Gerard describes it under the name of raphanus rusticanus, stating that it occurs wild in several parts of England. After referring to its medicinal uses, he says:

[T]he Horse Radish stamped with a little vinegar put thereto, is commonly used among the Germans for sauce to eat fish with and such like meats as we do mustard.[14]

Etymology and common names

The word horseradish is attested in English from the 1590s. It combines the word horse (formerly used in a figurative sense to mean strong or coarse) and the word radish.[15] Some sources say that the term originates from a mispronunciation of the German word "meerrettich" as "mareradish".[16][17][18] However, this hypothesis has been disputed, as there is no historical evidence of this term being used.[19]

In Central and Eastern Europe, horseradish is called chren, hren and ren (in various spellings like kren) in many Slavic languages, in Austria, in parts of Germany (where the other German name Meerrettich is not used), in North-East Italy, and in Yiddish (כריין transliterated as khreyn). It is common in Ukraine (under the name of хрін, khrin), in Belarus (under the name of хрэн, chren), in Poland (under the name of chrzan), in the Czech Republic (křen), in Slovakia (chren), in Russia (хрен, khren), in Hungary (torma), in Romania (hrean), in Lithuania (krienas), and in Bulgaria (under the name of хрян).

Cultivation

Horseradish is perennial in hardiness zones 2–9 and can be grown as an annual in other zones, although not as successfully as in zones with both a long growing season and winter temperatures cold enough to ensure plant dormancy. After the first frost in autumn kills the leaves, the root is dug and divided. The main root is harvested and one or more large offshoots of the main root are replanted to produce next year's crop. Horseradish left undisturbed in the garden spreads via underground shoots and can become invasive. Older roots left in the ground become woody, after which they are no longer culinarily useful, although older plants can be dug and re-divided to start new plants. The early season leaves can be distinctively different, asymmetric spiky, before the mature typical flat broad leaves start to be developed.

Pests and diseases

Introduced by accident, "cabbageworms", the larvae of Pieris rapae, are a common caterpillar pest in horseradish. Mature caterpillars chew large, ragged holes in the leaves leaving the large veins intact. Handpicking is an effective control strategy in home gardens.[20] Another common pest of horseradish is the mustard leaf beetle (Phaedon cochleariae).[21] These beetles are undeterred by the defense mechanisms produced by Brassicaceae plants like horseradish.[22]

Production

In the United States, horseradish is grown in several areas such as Eau Claire, Wisconsin, and Tule Lake, California. The most concentrated growth occurs in the Collinsville, Illinois region.[23]

30,000 metric tonnes of horseradish are produced in Europe annually, of which Hungary produces 12,000, making it the biggest single producer.[24]

Culinary uses

The distinctive pungent taste of horseradish is from the compound allyl isothiocyanate. Upon crushing the flesh of horseradish, the enzyme myrosinase is released and acts on the glucosinolates sinigrin and gluconasturtiin, which are precursors to the allyl isothiocyanate.[citation needed] The allyl isothiocyanate serves the plant as a natural defense against herbivores. Since allyl isothiocyanate is harmful to the plant itself, it is stored in the harmless form of the glucosinolate, separate from the enzyme myrosinase. When an animal chews the plant, the allyl isothiocyanate is released, repelling the animal.[25] Allyl isothiocyanate is an unstable compound, degrading over the course of days at 37 °C (99 °F).[26] Because of this instability, horseradish sauces lack the pungency of the freshly crushed roots.

Cooks may use the terms "horseradish" or "prepared horseradish" to refer to the mashed (or grated) root of the horseradish plant mixed with vinegar. Prepared horseradish is white to creamy-beige in color. It can be stored for up to 3 months under refrigeration,[27] but eventually will darken, indicating less flavour.[citation needed] The leaves of the plant are edible, either cooked or raw when young,[28] with a flavor similar but weaker than the roots.

On Passover, many Ashkenazi Jews use grated horseradish as a choice for Maror (bitter herbs) at the Passover Seder.[29]

Horseradish sauce

Horseradish sauce made from grated horseradish root and vinegar is a common condiment in the United Kingdom, in Denmark (with sugar added) and in Poland.[30] In the UK, it is usually served with roast beef, often as part of a traditional Sunday roast, but can be used in a number of other dishes, including sandwiches or salads. A variation of horseradish sauce, which in some cases may substitute the vinegar with other products like lemon juice or citric acid, is known in Germany as Tafelmeerrettich. Also available in the UK is Tewkesbury mustard, a blend of mustard and grated horseradish originating in medieval times and mentioned by Shakespeare (Falstaff says: "his wit's as thick as Tewkesbury Mustard" in Henry IV Part II[31]). A similar mustard, called Krensenf or Meerrettichsenf, is common in Austria and parts of Germany. In France, sauce au raifort is used in Alsatian cuisine. In Russia, horseradish root is usually mixed with grated garlic and a small amount of tomatoes for color (Khrenovina sauce).

In the United States, the term "horseradish sauce" refers to grated horseradish combined with mayonnaise or salad dressing. In Denmark, it is mixed with whipping cream and as such used on top of traditional Danish open sandwiches with beef (boiled or steaked) slices. Prepared horseradish is a common ingredient in Bloody Mary cocktails and in cocktail sauce and is used as a sauce or sandwich spread. Horseradish cream is a mixture of horseradish and sour cream and is served au jus for a prime rib dinner.[citation needed]

Vegetable

In Europe, there are two varieties of chrain. "Red" chrain is mixed with red beetroot and "white" chrain contains no beetroot. Chrain is a part of Christian Easter and Jewish Passover tradition (as maror) in Eastern and Central Europe. In the Christian tradition, horseradish is eaten during Eastertide (Paschaltide) as "is a reminder of the bitterness of Jesus' suffering" on Good Friday.[32]

- In parts of Southern Germany "kren" is a component of the traditional wedding dinner. It is served with cooked beef and a dip made from lingonberry to balance the slight hotness of the Kren.

- In Poland, a variety with red beetroot is called ćwikła z chrzanem or simply ćwikła.

- In Russia, a very popular ingredient for pickles (cucumbers, tomatoes, mushrooms).

- In Ashkenazi European Jewish cooking, beetroot horseradish is commonly served with gefilte fish.

- In Transylvania and other Romanian regions, red beetroot with horseradish is used as a salad served with lamb dishes at Easter called sfecla cu hrean.

- In Serbia, ren is an essential condiment with cooked meat and freshly roasted suckling pig.

- In Croatia, freshly grated horseradish (Croatian: Hren) is often eaten with boiled ham or beef.

- In Hungary, Slovenia, and in the adjacent Italian regions of Friuli-Venezia Giulia and nearby Italian region of Veneto, horseradish (often grated and mixed with sour cream, vinegar, hard-boiled eggs, or apples) is also a traditional Easter dish.

- In the Italian regions of Lombardy, Emilia-Romagna, and Piedmont, it is called barbaforte (strong beard) and is a traditional accompaniment to bollito misto; while in northeastern regions like Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol,[33] Veneto[34] and Friuli-Venezia Giulia,[35][36] it is still called kren or cren. In the southern region of Basilicata it is known as rafano and used for the preparation of rafanata, a main course made of horseradish, eggs, cheese and sausage.[37]

- Horseradish is also used as a main ingredient for soups. In Poland, horseradish soup is a common Easter Day dish.[38]

Relation to wasabi

Outside Japan, the Japanese condiment wasabi, although traditionally prepared from the true wasabi plant (Wasabia japonica), is now usually made with horseradish due to the scarcity of the wasabi plant.[39] The Japanese botanical name for horseradish is seiyōwasabi (セイヨウワサビ, 西洋山葵), or "Western wasabi". Both plants are members of the family Brassicaceae.

Nutritional content

In a 100-gram amount, prepared horseradish provides 48 calories and has high content of vitamin C with moderate content of sodium, folate and dietary fiber, while other essential nutrients are negligible in content.[40] In a typical serving of one tablespoon (15 grams), horseradish supplies no significant nutrient content.[40]

Horseradish contains volatile oils, notably mustard oil.[25]

Biomedical uses

The enzyme horseradish peroxidase (HRP), found in the plant, is used extensively in molecular biology and biochemistry primarily for its ability to amplify a weak signal and increase detectability of a target molecule.[41] HRP has been used in decades of research to visualize under microscopy and assess non-quantitatively the permeability of capillaries, particularly those of the brain.[42]

References

- ^ Smekalova, T. & Maslovky, O. (2011). "Horseradish". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011: e.T176596A7273339. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ "The Plant List, Armoracia rusticana P.Gaertn., B.Mey. & Scherb".

- ^ a b c Stace, C. A. (2019). New Flora of the British Isles (Fourth ed.). Middlewood Green, Suffolk, U.K.: C & M Floristics. ISBN 978-1-5272-2630-2.

- ^ "Flora of North America, Armoracia rusticana P. Gaertner, B. Meyer & Scherbius, Oekon. Fl. Wetterau. 2: 426. 1800".

- ^ "Flora of China, Armoracia rusticana P. Gaertner et al".

- ^ Altervista Flora Italiana, Rafano rusticano, Meerrettich, Armoracia rusticana P. Gaertn., B. Mey. & Scherb. includes photos and European distribution map

- ^ "Biota of North America Program 2014 county distribution map".

- ^ "Horseradish". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ Early Modern translators of Dioscurides offered various names.

- ^ "Pliny on Thlaspi or Persicon napy H.N. i. 37.113".

- ^ Courter, J. W.; Rhodes, A. M. (April–June 1969). "Historical notes on horseradish". Economic Botany. 23 (2): 156–164. doi:10.1007/BF02860621. JSTOR 4253036. S2CID 23966751.

- ^ Ann Leighton, American Gardens in the Eighteenth Century: 'For Use or Delight' , 1976, p.431.

- ^ Lyle, Katie Letcher (2010) [2004]. The Complete Guide to Edible Wild Plants, Mushrooms, Fruits, and Nuts: How to Find, Identify, and Cook Them (2nd ed.). Guilford, CN: FalconGuides. pp. 153–154. ISBN 978-1-59921-887-8. OCLC 560560606.

- ^ Phillips, Henry (1822). History of Cultivated Vegetables. H. Colburn and Co. p. 255. ISBN 978-1-4369-9965-6.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "Online Etymology Dictionary: horseradish". Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ "Horseradish History |". horseradish.org. Retrieved 2023-03-16.

- ^ Wright, Janine (2010). "The Herb Society of America's Essential Guide to Horseradish". Herb Society of America. Archived from the original on 5 April 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

- ^ Trinklein, David (1 July 2011). "Horseradish: America's Favorite Root?". Integrated Pest Management: University of Missouri. Archived from the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

- ^ "How Was Horseradish Named? Did Horses Eat It?". CulinaryLore. 2014-01-24. Retrieved 2023-03-16.

- ^ Suzanne Wold-Burkness and Jeff Hahn. "Caterpillar Pests of Cole Crops in Home Gardens". University of Minnesota. Archived from the original on 2007-10-02. Retrieved 2007-09-30.

- ^ Gross, Jürgen; Müller, Caroline; Vilcinskas, Andreas; Hilker, Monika (November 1998). "Antimicrobial Activity of Exocrine Glandular Secretions, Hemolymph, and Larval Regurgitate of the Mustard Leaf BeetlePhaedon cochleariae". Journal of Invertebrate Pathology. 72 (3): 296–303. doi:10.1006/jipa.1998.4781. PMID 9784354.

- ^ Friedrichs, Jeanne; Schweiger, Rabea; Geisler, Svenja; Mix, Andreas; Wittstock, Ute; Müller, Caroline (September 2020). "Novel glucosinolate metabolism in larvae of the leaf beetle Phaedon cochleariae". Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 124: 103431. doi:10.1016/j.ibmb.2020.103431. PMID 32653632.

- ^ Walters, S. Alan; Wahle, Elizabeth A. (2010-04-01). "Horseradish Production in Illinois". HortTechnology. 20 (2): 267–276. doi:10.21273/HORTTECH.20.2.267. ISSN 1943-7714.

- ^ Albert, Dénes (29 March 2021). "Hungary is Europe's horseradish production king". Remix News. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ a b Cole, Rosemary A. (1976). "Isothiocyanates, nitriles and thiocyanates as products of autolysis of glucosinolates in Cruciferae". Phytochemistry. 15 (5): 759–762. Bibcode:1976PChem..15..759C. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(00)94437-6.

- ^ Ohta, Yoshio; Takatani, Kenichi; Kawakishi, Shunro (1995). "Decomposition Rate of Allyl Isothiocyanate in Aqueous Solution". Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry. 59: 102–103. doi:10.1271/bbb.59.102.

- ^ Nathan, Joan. "Prepared Horseradish Recipe". NYT Cooking. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ Angier, Bradford (1974). Field Guide to Edible Wild Plants. Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole Books. p. 104. ISBN 0-8117-0616-8. OCLC 799792.

- ^ Kordova, Shoshana (12 April 2022). "What Goes on a Seder Plate?". Haaretz. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ Holland, Mina (2014). The Edible Atlas: Around the World in Thirty-Nine Cuisines. Canongate Books. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-85786-856-5.

- ^ "Henry IV, Part II, Scene 4". opensourceshakespeare.org. Archived from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ^ Silverman, Deborah Anders (2000). Polish-American Folklore. University of Illinois Press. p. 31-32. ISBN 978-0-252-02569-3.

- ^ Giambattista Azzolini, Vocabolario vernacolo-italiano pei distretti roveretano e trentino, Venezia, Tip. e calc. di Giuseppe Grimaldo, 1856, p. 120.

- ^ Giuseppe Boerio, Dizionario del dialetto veneziano, 3rd edition, Venezia, Reale tipografia di Giovanni Cecchini edit., 1867, p. 207.

- ^ Rafano rusticano in www.friul.net.

- ^ Jacopo Pirona, Vocabolario friulano, Venezia, coi tipi dello stabilimento Antonelli, 1871, p. 490.

- ^ Zanini De Vita, Oretta (2009). Encyclopedia of Pasta. University of California Press. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-520-25522-7. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

rafanata horseradish.

- ^ "Horseradish Soup Recipe Updated with Photographs – Polish Easter Food". Culture.polishsite.us. Archived from the original on 2011-09-30. Retrieved 2012-07-08.

- ^ Arnaud, Celia Henry (2010). "Wasabi: In condiments, horseradish stands in for the real thing". Chemical & Engineering News. 88 (12): 48. doi:10.1021/cen-v088n012.p048. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ a b "Nutrient content of prepared horseradish per 100 g". FoodData Central, US Department of Agriculture. 1 April 2018. Retrieved 9 August 2023.

- ^ Bladha, K. Wedelsbäck; Olssonb, K. M. (2011). "Introduction and use of horseradish (Armoracia rusticana) as food and medicine from antiquity to the present: Emphasis on the nordic countries". Journal of Herbs, Spices and Medicinal Plants. 17 (3): 197–213. doi:10.1080/10496475.2011.595055. S2CID 84556980.

- ^ Lossinsky, A. S.; Shivers, R. R. (2004). "Structural pathways for macromolecular and cellular transport across the blood-brain barrier during inflammatory conditions. Review". Histology and Histopathology. 19 (2): 535–64. doi:10.14670/HH-19.535. PMID 15024715.

External links

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Recent Comments