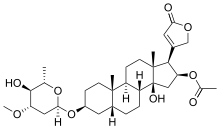

Asclepias is a genus of herbaceous, perennial, flowering plants known as milkweeds, named for their latex, a milky substance containing cardiac glycosides termed cardenolides, exuded where cells are damaged.[4][5][6] Most species are toxic to humans and many other species, primarily due to the presence of cardenolides. However, as with many such plants, some species feed upon them (e.g. their leaves) or from them (e.g. their nectar). The most notable of them is the monarch butterfly, which uses and requires certain milkweeds as host plants for their larvae.

The genus contains over 200 species distributed broadly across Africa, North America, and South America.[7] It previously belonged to the family Asclepiadaceae, which is now classified as the subfamily Asclepiadoideae of the dogbane family, Apocynaceae.

The genus was formally described by Carl Linnaeus in 1753,[8] who named it after Asclepius, the Greek god of healing.[9]

Flowers

Members of the genus produce some of the most complex flowers in the plant kingdom, comparable to orchids in complexity. Five petals reflex backwards revealing a gynostegium surrounded by a five-membrane corona. The corona is composed of a five-paired hood-and-horn structure with the hood acting as a sheath for the inner horn. Glands holding pollinia are found between the hoods. The size, shape and color of the horns and hoods are often important identifying characteristics for species in the genus Asclepias.[10]

Pollination in this genus is accomplished in an unusual manner. Pollen is grouped into complex structures called pollinia (or "pollen sacs"), rather than being individual grains or tetrads, as is typical for most plants. The feet or mouthparts of flower-visiting insects, such as bees, wasps, and butterflies, slip into one of the five slits in each flower formed by adjacent anthers. The bases of the pollinia then mechanically attach to the insect, so that a pair of pollen sacs can be pulled free when the pollinator flies off, assuming the insect is large enough to produce the necessary pulling force (if not, the insect may become trapped and die).[11] Pollination is effected by the reverse procedure, in which one of the pollinia becomes trapped within the anther slit. Large-bodied hymenopterans (bees, wasps) are the most common and best pollinators, accounting for over 50% of all Asclepias pollination,[12] whereas monarch butterflies are poor pollinators of milkweed.[5]

Asclepias species produce their seeds in pods termed follicles. The seeds, which are arranged in overlapping rows, bear a cluster of white, silky, filament-like hairs known as the coma[13] (often referred to by other names such as pappus, "floss", "plume", or "silk"). The follicles ripen and split open, and the seeds, each carried by its coma, are blown by the wind. Some, but not all, milkweeds also reproduce by clonal (or vegetative) reproduction.

Selected species

| Image | Scientific name | Common name | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Asclepias albicans | Whitestem milkweed | Native to the Mojave and Sonoran deserts |

|

Asclepias amplexicaulis | Blunt-leaved milkweed | Native to central and eastern United States |

|

Asclepias asperula | Antelope horns | Native to American southwest and northern Mexico |

|

Asclepias californica | California milkweed | Native to central and southern California |

|

Asclepias cordifolia | Heart-leaf milkweed | Native to the Sierra Nevada and Cascade Range up to 2,000 m (6,600 ft). |

|

Asclepias cryptoceras | Pallid milkweed | Native to the western United States. |

|

Asclepias curassavica | Scarlet milkweed, tropical milkweed, bloodflower, bastard ipecacuanha | Native to the American tropics, introduced to other continents |

|

Asclepias curtissii | Curtiss's milkweed | Endemic to sandy areas of Florida |

|

Asclepias eriocarpa | Woollypod milkweed | Native to California, Baja California, and Nevada |

|

Asclepias erosa | Desert milkweed | Native to California, Arizona, and Baja California |

|

Asclepias exaltata | Poke milkweed | Native to eastern North America |

|

Asclepias fascicularis | Narrow-leaf milkweed | Native to Western United States |

|

Asclepias hirtella | Tall green milkweed | |

|

Asclepias humistrata | Sandhill milkweed | Native to southeastern United States |

|

Asclepias incarnata | Swamp milkweed | Native to wetlands of North America |

|

Asclepias lanceolata | Lanceolate milkweed (Cedar Hill milkweed) | Native to coastal plain of eastern United States from Texas to New Jersey |

|

Asclepias linaria | Pine needle milkweed | Native to Mojave and Sonoran deserts |

|

Asclepias meadii | Mead's milkweed | Native to midwestern United States |

|

Asclepias nyctaginifolia | Mojave milkweed | native to the American southwest |

|

Asclepias purpurascens | Purple milkweed | Native to eastern, southern, and midwestern United States |

|

Asclepias prostrata | Prostrate milkweed | Native to Texas and northern Mexico |

|

Asclepias quadrifolia | Four-leaved milkweed | Native to eastern United States and Canada |

|

Asclepias rubra | Red milkweed | |

|

Asclepias solanoana | Serpentine milkweed | Native to northern California |

|

Asclepias speciosa | Showy milkweed | Native to western United States and Canada |

|

Asclepias subulata | Rush milkweed | Native to southwestern North America |

|

Asclepias subverticillata | Horsetail milkweed[14] | |

|

Asclepias sullivantii | Sullivant's milkweed | |

|

Asclepias syriaca | Common milkweed | |

|

Asclepias texana | Texas milkweed | |

|

Asclepias tuberosa | Butterfly weed, pleurisy root | |

|

Asclepias uncialis | Wheel milkweed | |

|

Asclepias variegata | White milkweed | |

|

Asclepias verticillata | Whorled milkweed | |

|

Asclepias viridiflora | Green milkweed | |

|

Asclepias viridis | Green antelopehorn, spider milkweed | |

|

Asclepias welshii | Welsh's milkweed |

There are also 12 species of Asclepias in South America, among them: A. barjoniifolia, A. boliviensis, A. curassavica, A. mellodora, A. candida, A. flava, and A. pilgeriana.

Ecology

Milkweeds are an important nectar source for native bees, wasps, and other nectar-seeking insects, though non-native honey bees commonly get trapped in the stigmatic slits and die.[11][15] Milkweeds are also the larval food source for monarch butterflies and their relatives, as well as a variety of other herbivorous insects (including numerous beetles, moths, and true bugs) specialized to feed on the plants despite their chemical defenses.[5]

Milkweeds use three primary defenses to limit damage caused by caterpillars: hairs on the leaves (trichomes), cardenolide toxins, and latex fluids.[16] Data from a DNA study indicate that, generally, more recently evolved milkweed species ("derived" in botany parlance) use these preventive strategies less but grow faster than older species, potentially regrowing faster than caterpillars can consume them.[17][18][19]

Research indicates that the very high cardenolide content of Asclepias linaria reduces the impact of the Ophryocystis elektroscirrha (OE) parasite on the monarch butterfly, Danaus plexippus. The OE parasite causes holes to form in the wings of fully developed monarch butterflies. This causes weakened endurance and an inability to migrate. The parasite only infects monarchs when they are larvae and caterpillars, but the detriment is when they are in their butterfly form.[20] By contrast, some species of Asclepias are extremely poor sources of cardenolides, such as Asclepias fascicularis, Asclepias tuberosa, and Asclepias angustifolia.[citation needed]

Monarch butterfly conservation and milkweeds

The leaves of Asclepias species are a food source for monarch butterfly larvae and some other milkweed butterflies.[5] These plants are often used in butterfly gardening and monarch waystations in an effort to help increase the dwindling monarch population.[21]

However, some milkweed species are not suitable for butterfly gardens and monarch waystations. For example, A. curassavica, or tropical milkweed, is often planted as an ornamental in butterfly gardens outside of its native range of Mexico and Central America. Year-round plantings of this species in the United States are controversial and criticised, as they may lead to new overwintering sites along the U.S. Gulf Coast and the consequent year-round breeding of monarchs.[22] This is thought to adversely affect migration patterns, and to cause a dramatic build-up of the dangerous parasite, Ophryocystis elektroscirrha.[23] New research also has shown that monarch larvae reared on tropical milkweed show reduced migratory development (reproductive diapause), and when migratory adults are exposed to tropical milkweed, it stimulates reproductive tissue growth.[24]

Because of this, it is most often suggested to grow milkweeds that are native to the geographical area they are planted in to prevent negative impacts on monarch butterflies.[25][26]

Monarch caterpillars do not favor butterfly weed (A. tuberosa), perhaps because the leaves of that milkweed species contain very little cardenolide.[27] Some other milkweeds may have similar characteristics.

Uses

Milkweeds are not grown commercially in large scale, but the plants have had many uses throughout human history.[5] Milkweeds have a long history of medicinal, every day, and military use. The Omaha people from Nebraska, the Menomin from Wisconsin and upper Michigan, the Dakota from Minnesota, and the Ponca people from Nebraska, traditionally used common milkweed (A. syriaca) for medicinal purposes.[citation needed] The bast fibers of some species can be used for rope. The Miwok people of northern California used heart-leaf milkweed (A. cordifolia) for its stems, which they dried and used for cords, strings and ropes.[28]

The fine, silky fluff attached to milkweed seeds, which allows them to be distributed long distances on the wind, is known as floss. Milkweed floss is incredibly difficult to spin due to how short and smooth the filaments are, but blending it with as little as 25% wool or other fiber can produce workable yarn.[29]

A study of the insulative properties of various materials found that milkweed floss was outperformed by other materials in terms of insulation, loft, and lumpiness, but it scored well when mixed with down feathers.[30] The milkweed filaments from the coma (the "floss") are hollow and coated with wax, and have good insulation qualities. During World War II, more than 5,000 t (5,500 short tons) of milkweed floss was collected in the US as a substitute for kapok.[31][32] Milkweed is grown commercially as a hypoallergenic filling for pillows[33] and as insulation for winter coats.[34] Using milkweed floss for these purposes could provide a plant-based alternative to down and promote the growth of milkweed in areas where it has declined, though there is some concern that the environmental impacts could be negative if monoculture is used.[35] Asclepias is also known as "Silk of America"[36] which is a strand of common milkweed (A. syriaca) gathered mainly in the valley of the Saint Lawrence River in Canada. Milkweed floss can be used in thermal insulation and acoustic insulation. The floss is also highly buoyant and water-repellent, but absorbs oil readily.[37] Due to its oil-absorbing properties, it can be used for oil spill cleanup.[38][39][40]

Milkweed latex contains about two percent latex, and during World War II both Nazi Germany and the US attempted to use it as a source of natural rubber, although no record of large-scale success has been found.[41]

Many milkweed species also contain cardiac glycoside poisons that inhibit animal cells from maintaining a proper K+, Ca2+ concentration gradient.[6] As a result, many peoples of South America and Africa used arrows poisoned with these glycosides to fight and hunt more effectively. Some milkweeds are toxic enough to cause death when animals consume large quantities of the plant. Some milkweeds also cause mild dermatitis in some who come in contact with them. Nonetheless, some species can be made edible if properly processed.[5]

References

- ^ "Taxon: Asclepias L." Germplasm Resources Information Network. United States Department of Agriculture. 13 March 2003. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ^ "Asclepias". NCBI taxonomy. Bethesda, MD: National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ^ "Asclepias L. | Plants of the World Online | Kew Science". Plants of the World Online. Retrieved 12 February 2024.

- ^ Singh, B.; Rastogi, R. P. (1970). "Cardenolides-glycosides and genins". Phytochemistry. 9 (2): 315–331. Bibcode:1970PChem...9..315S. doi:10.1016/s0031-9422(00)85141-9.

- ^ a b c d e f Agrawal, Anurag (7 March 2017). Monarchs and Milkweed: A Migrating Butterfly, a Poisonous Plant, and Their Remarkable Story of Coevolution. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400884766.

- ^ a b Agrawal, Anurag A.; Petschenka, Georg; Bingham, Robin A.; Weber, Marjorie G.; Rasmann, Sergio (1 April 2012). "Toxic cardenolides: chemical ecology and coevolution of specialized plant–herbivore interactions". New Phytologist. 194 (1): 28–45. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.04049.x. ISSN 1469-8137. PMID 22292897.

- ^ "Asclepias L." Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ^ "Asclepias". ipni.org. International Plant Names Index. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ^ Quattrocchi, Umberto (29 November 1999). CRC World Dictionary of Plant Names: Common Names, Scientific Names, Eponyms, Synonyms, and Etymology. CRC Press. p. 211. ISBN 978-0-8493-2673-8.

Latin asclepias and Greek asklepias for the common swallowwort; Asclepius, Greek god of medicine, the worship of Asclepius was centered in Epidaurus. See W.K.C. Guthrie, The Greeks and Their Gods, 1950; Carl Linnaeus, Species Plantarum. 214. 1753 and Genera Plantarum. Ed. 5. 102. 1754.

- ^ http://orbisec.com/milkweed-flower-morphology-and-terminology/ Milkweed Flower Morphology

- ^ a b Robertson, C. (1887) Insect relations of certain asclepiads. I. Botanical Gazette 12: 207–216

- ^ Ollerton, J. & S. Liede. 1997. Pollination systems in the Asclepiadaceae: a survey and preliminary analysis. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society (1997), 62: 593–610.

- ^ Sacchi, C.F. (1987) Variability in dispersal ability of Common Milkweed, Asclepias syriaca, seeds, Oikos Vol. 49, pp. 191–198

- ^ Asclepias subverticillata (A. Gray) Vail, USDA PLANTS

- ^ Frost, S.W. (1965). "Insects and pollinia". Ecology. 46 (4): 556–558. Bibcode:1965Ecol...46..556F. doi:10.2307/1934896. JSTOR 1934896.

- ^ Agrawal, Anurag A.; Ali, Jared G.; Rasmann, Sergio; Fishbein, Mark (2015). "4 - Macroevolutionary Trends in the Defense of Milkweeds against Monarchs - Latex, Cardenolides, and Tolerance of Herbivory". In Oberhauser, Karen (ed.). Monarchs in a changing world: biology and conservation of an iconic butterfly. Ithaca London: Comstock Publishing, a division of Cornell University Press. pp. 47–59. ISBN 978-0-8014-5560-5. OCLC 918150494.

- ^ Ramanujan, Krishna (Winter 2008). "Discoveries: Milkweed evolves to shrug off predation". Northern Woodlands. 15 (4): 56.

- ^ Agrawal, Anurag A.; Fishbein, Mark (22 July 2008). "Phylogenetic escalation and decline of plant defense strategies". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (29): 10057–10060. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10510057A. doi:10.1073/pnas.0802368105. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 2481309. PMID 18645183.

- ^ Callis-Duehl, Kristine; Vittoz, Pascal; Defossez, Emmanuel; Rasmann, Sergio (20 December 2016). "Community-level relaxation of plant defenses against herbivores at high elevation". Plant Ecology. 218 (3). Springer: 291–304. doi:10.1007/s11258-016-0688-4. ISSN 1385-0237. S2CID 34282179.

- ^ "We're losing monarchs fast—here's why". Animals. 21 December 2018. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ (1) "Butterfly Gardening: Introduction". University of Kansas: Monarch Watch. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

(2) "Monarch Watch: Monarch Waystation Program". University of Kansas, Entomology Department. Archived from the original on 18 November 2019. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

(3) "Monarch Garden Plants" (PDF). San Francisco, California: Pollinator Partnership. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 March 2020. Retrieved 9 March 2020. - ^ Howard, Elizabeth; Aschen, Harlen; Davis, Andrew K. (2010). "Citizen Science Observations of Monarch Butterfly Overwintering in the Southern United States". Psyche: A Journal of Entomology. 2010: 1. doi:10.1155/2010/689301.

- ^ Satterfield, D. A.; Maerz, J. C.; Altizer, S (2015). "Loss of migratory behaviour increases infection risk for a butterfly host". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 282 (1801): 20141734. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.1734. PMC 4308991. PMID 25589600.

- ^ Majewska, Ania A.; Altizer, Sonia (16 August 2019). "Exposure to Non-Native Tropical Milkweed Promotes Reproductive Development in Migratory Monarch Butterflies". Insects. 10 (8): 253. doi:10.3390/insects10080253. PMC 6724006. PMID 31426310.

- ^ "Milkweed for Monarchs". The National Wildlife Federation.

- ^ "Milkweed Map - discover native milkweed". GROW MILKWEED PLANTS. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- ^ (1) Pocius, Victoria M.; Debinski, Diane M.; Pleasants, John M.; Bidne, Keith G.; Hellmich, Richard L. (8 January 2018). "Monarch butterflies do not place all of their eggs in one basket: oviposition on nine Midwestern milkweed species". Ecosphere. 9 (1). Ecological Society of America (ESA): 1–13. Bibcode:2018Ecosp...9E2064P. doi:10.1002/ecs2.2064.

In our study, the least preferred milkweed species A. tuberosa (no choice; Fig. 2) and A. verticillata (choice; Fig. 3A) both have low cardenolide levels recorded in the literature (Roeske et al. 1976, Agrawal et al. 2009, 2015, Rasmann and Agrawal 2011)

(2) Abugattas, Alonzo (3 January 2017). "Monarch Way Stations". Capital Naturalist. Archived from the original on 5 June 2017. Retrieved 5 June 2017 – via Blogger.It is the least favored by monarch caterpillars though because it has very little toxin (cardiac glycosides) in its leaves, but other butterflies and adult monarchs love it as a nectar source.

.

(3) "Butterfly Weed: Asclepias tuberosa" (PDF). Becker County, Minnesota: Becker Soil and Water Conservation District. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 September 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2020.Unlike other milkweeds, this plant has a clear sap, and the level of toxic cardiac glycosides is consistently low (although other toxic compounds may be present).

. - ^ Johnson, Glen A (2019). Milkweed of the United States, including Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands. Amazon KDP. p. 7. ISBN 9781081170653.

- ^ Nehring, Julia. "The potential of milkweed floss as a natural fiber in the textile industry" (PDF). Center for Undergraduate Research.

- ^ McCullough, Elizabeth A. (April 1991). "Evaluation of Milkweed Floss as an Insulative Fill Material". Textile Research Journal. 61 (4): 203–210. doi:10.1177/004051759106100403. S2CID 17783131.

- ^ Hauswirth, Katherine (26 October 2008). "The Heroic Milkweed". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- ^ Wykes, Gerald (4 February 2014). "A Weed Goes to War, and Michigan Provides the Ammunition". MLive Media Group. Michigan History Magazine. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- ^ Evangelista, R.L. (2007). "Milkweed seed wing removal to improve oil extraction". Industrial Crops and Products. 25 (2): 210–217. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2006.10.002.

- ^ Bernstein, Jaela (13 October 2016). "How a Quebec company used a weed to create a one-of-a-kind winter coat". CBC News. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- ^ Bauck, Whitney (23 January 2020). "THE FUTURE OF SUSTAINABLE MATERIALS: MILKWEED FLOSS". Fashionista.com.

- ^ Charles Sigisbert, Sonnini (1810). Traité de l'asclépiade.

- ^ Augustine, Kathy. "Monarchs, Milkweed, and You". spinoffmagazine.com. Spin Off Magazine.

- ^ Choi, Hyung Min; Cloud, Rinn M. (1992). "Natural sorbents in oil spill clean-up". Environmental Science & Technology. 26 (4): 772. Bibcode:1992EnST...26..772C. doi:10.1021/es00028a016.

- ^ "La soie d'Amérique passe en production industrielle". Radio Canada. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- ^ "Milkweed touted as oil-spill super-sucker — with butterfly benefits". cbc.ca. 2 December 2014.

- ^ Beckett, R. E.; Stitt, R. S. (May 1935). The desert milkweed (Asclepias subulata) as a possible source of rubber (Technical report). United States Department of Agriculture. 73.

- Everitt, J.H.; Lonard, R.L.; Little, C.R. (2007). Weeds in South Texas and Northern Mexico. Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press. ISBN 0-89672-614-2

Recent Comments