Cedrus deodara, the deodar cedar, Himalayan cedar, or deodar,[2] is a species of cedar native to the Himalayas.

Description

It is a large evergreen coniferous tree reaching 40–50 metres (131–164 feet) tall, exceptionally 60 m (197 ft) with a trunk up to 3 m (10 ft) in diameter. It has a conic crown with level branches and drooping branchlets.[3]

The leaves are needle-like, mostly 2.5–5 centimetres (1–2 inches) long, occasionally up to 7 cm (3 in) long, slender (1 millimetre or 1⁄32 in thick), borne singly on long shoots, and in dense clusters of 20–30 on short shoots; they vary from bright green to glaucous blue-green in colour. The female cones are barrel-shaped, 7–13 cm (2+3⁄4–5 in) long and 5–9 cm (2–3+1⁄2 in) broad, and disintegrate when mature (in 12 months) to release the winged seeds. The male cones are 4–6 cm (1+1⁄2–2+1⁄4 in) long, and shed their pollen in autumn.[3]

-

Young tree in India

-

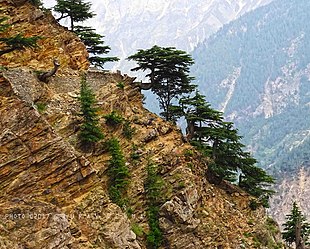

Older tree in India

-

Trunk

-

Close-up of leaves

-

Leaves and female cone

-

Top view of cone

Chemistry

The bark of Cedrus deodara contains large amounts of taxifolin.[4] The wood contains cedeodarin, ampelopsin, cedrin, cedrinoside,[5] and deodarin (3′,4′,5,6-tetrahydroxy-8-methyl dihydroflavonol).[6] The main components of the needle essential oil include α-terpineol (30.2%), linalool (24.47%), limonene (17.01%), anethole (14.57%), caryophyllene (3.14%), and eugenol (2.14%).[7] The deodar cedar also contains lignans[8] and the phenolic sesquiterpene himasecolone, together with isopimaric acid.[9] Other compounds have been identified, including (−)-matairesinol, (−)-nortrachelogenin, and a dibenzylbutyrolactollignan (4,4',9-trihydroxy-3,3'-dimethoxy-9,9'-epoxylignan).[10]

Etymology

The botanical name, which is also the English common name, is derived from the Sanskrit term devadāru, which means "wood of the gods", a compound of deva "god" and dāru "wood and tree".[11][12]

Distribution and habitat

The species natively occurs in East-Afghanistan, South Western Tibet, Western Nepal, Northern Pakistan, and North-Central India.[13][1]

It grows at altitudes of 1,500–3,200 m (5,000–10,000 ft).

Reproduction

“Deodar is a wind-pollinated monoecious species”.[14]

Cultivation

It is widely grown as an ornamental tree, often planted in parks and large gardens for its drooping foliage. General cultivation is limited to areas with mild winters, with trees frequently killed by temperatures below about −25 °C (−13 °F), limiting it to USDA zone 7 and warmer for reliable growth.[15] It can succeed in rather cool-summer climates, as in Ushuaia, Argentina.[16]

The most cold-tolerant trees originate in the northwest of the species' range in Kashmir and Paktia Province, Afghanistan. Selected cultivars from this region are hardy to USDA zone 7 or even zone 6, tolerating temperatures down to about −30 °C (−22 °F).[15] Named cultivars from this region include 'Eisregen', 'Eiswinter', 'Karl Fuchs', 'Kashmir', 'Polar Winter', and 'Shalimar'.[17][18] Of these, 'Eisregen', 'Eiswinter', 'Karl Fuchs', and 'Polar Winter' were selected in Germany from seed collected in Paktia; 'Kashmir' was a selection of the nursery trade, whereas 'Shalimar' originated from seeds collected in 1964 from Shalimar Gardens, Kashmir and propagated at the Arnold Arboretum.[17]

C. deodara[19] and the three cultivars 'Feelin' Blue',[20] 'Pendula'[21] and 'Aurea'[22] have gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit (confirmed 2021).[23]

Uses

Construction material

Deodar is in great demand as building material because of its durability, rot-resistant character and fine, close grain, which is capable of taking a high polish. Its historical use to construct religious temples and in landscaping around temples is well recorded. Its rot-resistant character also makes it an ideal wood for constructing the well-known houseboats of Srinagar, Kashmir. In Pakistan and India, during the British colonial period, deodar wood was used extensively for construction of barracks, public buildings, bridges, canals and railway cars.[24] Despite its durability, it is not a strong timber, and its brittle nature makes it unsuitable for delicate work where strength is required, such as chair-making.[citation needed]

Herbal Ayurveda

C. deodara is used in Ayurvedic medicine.[24]

The inner wood is aromatic and used to make incense. Inner wood is distilled into essential oil. As insects avoid this tree, the essential oil is used as insect repellent on the feet of horses, cattle and camels. It also has antifungal properties and has some potential for control of fungal deterioration of spices during storage.[citation needed] The outer bark and stem are astringent.[25]

Because of its antifungal and insect repellent properties, rooms made of deodar cedar wood are used to store meat and food grains like oats and wheat in Shimla, Kullu, and Kinnaur district of Himachal Pradesh.

Cedar oil is often used for its aromatic properties, especially in aromatherapy. It has a characteristic woody odor which may change somewhat in the course of drying out. The crude oils are often yellowish or darker in color. Its applications include soap perfumes, household sprays, floor polishes, and insecticides, and is also used in microscope work as a clearing oil.[25]

Incense

The gum of the tree is used to make rope incense in Nepal and Tibet.[26]

Culture

Among Hindus, as the etymology of deodar suggests, it is worshiped as a divine tree. Deva, the first half of the Sanskrit term, means divine, deity, or deus. Dāru, the second part, is cognate with (related to) the words durum, druid, tree, and true.[24][self-published source?] Several Hindu legends refer to this tree. For example, Valmiki Ramayan reads:[27]

In the stands of Lodhra trees,[28] Padmaka trees [29] and in the woods of Devadaru, or Deodar trees, Ravana is to be searched there and there, together with Sita. [4-43-13]

The deodar is the national tree of Pakistan,[30] and the state tree of Himachal Pradesh, India.

Under the Deodars was an 1889 short story collection by Rudyard Kipling.[31]

The 1902 musical A Country Girl featured a song called "Under the Deodar."[32]

See also

References

- ^ a b Farjon, A. (2013). "Cedrus deodara". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013: e.T42304A2970751. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-1.RLTS.T42304A2970751.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ "Cedrus deodara". Germplasm Resources Information Network. Agricultural Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ a b Aljos, Farjon (1990). Pinaceae: drawings and descriptions of the genera Abies, Cedrus, Pseudolarix, Keteleeria, Nothotsuga, Tsuga, Cathaya, Pseudotsuga, Larix and Picea. Koenigstein: Koeltz Scientific Books. ISBN 978-3-87429-298-6.[page needed]

- ^ Willför, Stefan; Ali, Mumtaz; Karonen, Maarit; Reunanen, Markku; Arfan, Mohammad; Harlamow, Reija (2009). "Extractives in bark of different conifer species growing in Pakistan". Holzforschung. 63 (5): 551–8. doi:10.1515/HF.2009.095. S2CID 97003177.

- ^ Agrawal, P.K.; Agarwal, S.K.; Rastogi, R.P. (1980). "Dihydroflavonols from Cedrus deodara". Phytochemistry. 19 (5): 893–6. doi:10.1016/0031-9422(80)85133-8.

- ^ Adinarayana, D.; Seshadri, T.R. (1965). "Chemical investigation of the stem-bark of Cedrus deodara". Tetrahedron. 21 (12): 3727–30. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)96989-3.

- ^ Zeng, Wei-Cai; Zhang, Zeng; Gao, Hong; Jia, Li-Rong; He, Qiang (2012). "Chemical Composition, Antioxidant, and Antimicrobial Activities of Essential Oil from Pine Needle (Cedrus deodara)". Journal of Food Science. 77 (7): C824–9. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3841.2012.02767.x. PMID 22757704.

- ^ Agrawal, P.K.; Rastogi, R.P. (1982). "Two lignans from Cedrus deodara". Phytochemistry. 21 (6): 1459–1461. doi:10.1016/0031-9422(82)80172-6.

- ^ Agarwal, P.K.; Rastogi, R.P. (1981). "Terpenoids from Cedrus deodara". Phytochemistry. 20 (6): 1319–21. doi:10.1016/0031-9422(81)80031-3.

- ^ Tiwari, AK; Srinivas, PV; Kumar, SP; Rao, JM (2001). "Free radical scavenging active components from Cedrus deodara". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 49 (10): 4642–5. doi:10.1021/jf010573a. PMID 11600001.

- ^ Shinde, U. A.; Phadke, A. S.; Nair, A. M.; Mungantiwar, A. A.; Dikshit, V. J.; Saraf, M. N. (1999-06-01). "Membrane stabilizing activity — a possible mechanism of action for the anti-inflammatory activity of Cedrus deodara wood oil". Fitoterapia. 70 (3): 251–257. doi:10.1016/S0367-326X(99)00030-1. ISSN 0367-326X.

- ^ Mehta, Devanssh (2012-01-01). "An insight into traditional system of medicine".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Kumar, Avadhesh; Singh, Vandana; Chaudhary, Amrendra Kumar (2011-03-24). "Gastric antisecretory and antiulcer activities of Cedrus deodara (Roxb.) Loud. in Wistar rats". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 134 (2): 294–297. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2010.12.019. ISSN 0378-8741. PMID 21182918.

- ^ Sharma, C. M., & Khanduri, V. P. (2011). Pollen cone characteristics, pollen yield and pollen-mediated gene flow in Cedrus deodara. Current Science (Bangalore), 102(3), 394–397

- ^ a b Ødum, S. (1985). Report on frost damage to trees in Denmark after the severe 1981/82 and 1984/85 winters. Denmark: Hørsholm Arboretum.[page needed]

- ^ "Trees Near Their Limits".

- ^ a b Humphrey James, Welch (1993). Haddows, Gordon (ed.). The World Checklist of Conifers. Bromyard: Landsman's Bookshop. ISBN 978-0-900513-09-1.

- ^ Gerd, Krüssmann (1983). Handbuch der Nadelgehölze (in German) (2nd ed.). Berlin: Parey. ISBN 978-3-489-62622-0.[page needed]

- ^ "RHS Plantfinder - Cedrus deodar". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ "RHS Plantfinder - Cedrus deodara 'Feelin' Blue'". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ "RHS Plantfinder - Cedrus deodara 'Pendula'". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- ^ "RHS Plantfinder - Cedrus deodara 'Aurea'". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ "AGM Plants - Ornamental" (PDF). Royal Horticultural Society. December 2020. pp. 18, 19. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- ^ a b c McGowan, Chris (March 5, 2008). "The Deodar Tree: the Himalayan 'Tree of God'".

- ^ a b "Cedarwood Oils". Flavours and fragances of plant origin. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 1995. ISBN 92-5-103648-9. Archived from the original on 2011-06-18. Retrieved 2008-08-26.

- ^ Andrews, Arden Fanning (2021-09-10). "An Incense for Every Occasion". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-12-14.

- ^ "Valmiki Ramayana - Kishkindha Kanda". www.valmikiramayan.net.

- ^ Symplocos racemosa

- ^ Wild Himalayan Cherry

- ^ "Pakistan". Archived from the original on 2016-11-28.[non-primary source needed]

- ^ Kipling, Rudyard (September 1, 2001). "Under the Deodars" – via Project Gutenberg.

- ^ "Shazam". Shazam.

Recent Comments