Yucca is a genus of perennial shrubs and trees in the family Asparagaceae, subfamily Agavoideae.[2] Its 40–50 species are notable for their rosettes of evergreen, tough, sword-shaped leaves and large terminal panicles of white or whitish flowers. They are native to the Americas and the Caribbean in a wide range of habitats, from humid rainforest and wet subtropical ecosystems to the hot and dry (arid) deserts and savanna.

Early reports of the species were confused with the cassava (Manihot esculenta).[3] Consequently, Linnaeus mistakenly derived the generic name from the Taíno word for the latter, yuca.[4] The Aztecs living in Mexico since before the Spanish arrival, in Nahuatl, call the local yucca species (Yucca gigantea) iczotl, which gave the Spanish izote.[5][6] Izote is also used for Yucca filifera.[7]

Distribution

The natural distribution range of the genus Yucca (49 species and 24 subspecies) covers a vast area of the Americas. The genus is represented throughout Mexico and extends into Guatemala (Yucca guatemalensis). It also extends to the north through Baja California in the west, northwards into the southwestern United States, through the drier central states as far north as southern Alberta in Canada (Yucca glauca ssp. albertana).

Yucca is also native northward to the coastal lowlands and dry beach scrub of the coastal areas of the southeastern United States, along the Gulf of Mexico and South Atlantic States from coastal Texas to Maryland.

Yuccas have adapted to an equally vast range of climatic and ecological conditions. They are found in rocky deserts and badlands, in prairies and grassland, in mountainous regions, woodlands, in coastal sands (Yucca filamentosa), and even in subtropical and semitemperate zones. Several species occur in humid tropical zones (Yucca lacandonica) but most species occur in arid conditions, with the deserts of North America being regarded as the center of diversity for the genus.[8]

Ecology

Yuccas have a very specialized, mutualistic pollination system; being pollinated by yucca moths (family Prodoxidae); the insect transfers the pollen from the stamens of one plant to the stigma of another, and at the same time lays an egg in the flower; the moth larva then feeds on some of the developing seeds, always leaving enough seed to perpetuate the species. Certain species of the yucca moth have evolved antagonistic features against the plant. They do not assist in the plant's pollination efforts while continuing to lay their eggs in the plant for protection.[9]

Yucca species are the host plants for the caterpillars of the yucca giant-skipper (Megathymus yuccae),[10] ursine giant-skipper (Megathymus ursus),[11] and Strecker's giant-skipper (Megathymus streckeri).[12]

Beetle herbivores include yucca weevils, in the Curculionidae.

Uses

Yuccas are widely grown as ornamental plants in gardens. Many species also bear edible parts, including fruits, seeds, flowers, flowering stems,[13] and (more rarely) roots. References to yucca root as food often arise from confusion with the similarly pronounced, but botanically unrelated, yuca, also called cassava or manioc (Manihot esculenta). Roots of soaptree yucca (Yucca elata) are high in saponins and are used as a shampoo in Native American rituals. Dried yucca leaves and trunk fibers have a low ignition temperature, making the plant desirable for use in starting fires via friction. The stem (when dried) that sports the flowers is often used in conjunction with a sturdy piece of cedar for fire-making.[14] In rural Appalachian areas, species such as Yucca filamentosa are referred to as "meat hangers". With their sharp-spined tips, the tough, fibrous leaves were used to puncture meat and knotted to form a loop with which to hang meat for salt curing or in smokehouses. The fibers can be used to make domestic items[15] or for manufacturing cordage,[16] be it sewing-thread or rope.[citation needed] Yucca extract is also used as a foaming agent in some beverages such as root beer and soda.[17][18] Yucca powder and sap are derived from the logs of the plant; such extracts can be produced by mechanical squeezing and subsequent evaporation of the sap, and are widely used in food, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals [19]

Gastronomy

The flower petals are commonly eaten in Central America, but the plant's reproductive organs (the anthers and ovaries) are first removed because of their bitterness.[20] The petals are blanched for 5 minutes, and then cooked a la mexicana (with tomato, onion, chili) or in tortitas con salsa (egg-battered patties with green or red sauce). In Guatemala, they are boiled and eaten with lemon juice.[20]

In El Salvador, the tender tips of stems are eaten and known locally as cogollo de izote.[20]

Cultivation

The most common houseplant yucca is Yucca gigantea.[21]

Yuccas are widely grown as architectural plants providing a dramatic accent to landscape design. They tolerate a range of conditions but are best grown in full sun in subtropical or mild temperate areas. In gardening centres and horticultural catalogues, they are usually grouped with other architectural plants such as cordylines and phormiums.[22]

Several species of yucca can be grown outdoors in temperate climates, including:-[22]

Symbolism

The yucca flower is the state flower of New Mexico in the southwest United States. No species name is given in the citation; however, the New Mexico Centennial Blue Book from 2012 references the soaptree yucca (Yucca elata) as one of the more widespread species in New Mexico.[N 1]

The Yucca flower is also the national flower of El Salvador, where it is known as flor de izote.[23]

Species

As of February 2012, the World Checklist of Selected Plant Families recognizes 49 species of Yucca and several hybrids:[24]

| Plant | Flowers | Species name | Common name |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Yucca aloifolia L. (Type species) (syn. Yucca yucatana) | Aloe yucca, Spanish bayonet |

|

|

Yucca angustissima Engelm. ex Trel. (including Yucca kanabensis) | Narrowleaf yucca, Spanish bayonet |

|

|

Yucca arkansana Trel. | |

|

|

Yucca baccata Torr. (including Yucca thornberi) | Banana yucca, datil |

|

|

Yucca baileyi Wooton & Standl. (syn. Yucca standleyi McKelvey) | |

|

|

Yucca brevifolia Engelm. | Joshua tree |

|

Yucca campestris McKelvey | ||

|

Yucca capensis L.W.Lenz | ||

|

Yucca carnerosana (Trel.) McKelvey | ||

|

|

Yucca cernua E.L.Keith | |

|

Yucca coahuilensis Matuda & I.L.Pina | ||

|

Yucca constricta Buckley | Buckley's yucca | |

|

|

Yucca decipiens Trel. | Palma china |

|

Yucca declinata Laferr. | ||

|

Yucca desmetiana Baker | ||

|

|

Yucca elata (Engelm.) Engelm. | Soaptree yucca |

|

|

Yucca endlichiana Trel. | |

|

Yucca faxoniana Sarg. (syn. Yucca torreyi) | Torrey yucca | |

|

|

Yucca filamentosa L. | Spoonleaf yucca, filament yucca, or Adam's needle |

|

|

Yucca filifera Chabaud | Palma china |

|

Yucca flaccida Haw. | Flaccid leaf yucca | |

|

|

Yucca gigantea Lem. (syn. Yucca guatemalensis) | Spineless yucca |

|

|

Yucca glauca Nutt. | Great Plains yucca |

|

Yucca gloriosa L. (including Yucca recurvifolia) | Moundlily yucca, Adam's needle, Spanish dagger | |

|

Yucca grandiflora Gentry | Sahuiliqui yucca | |

|

|

Yucca harrimaniae Trel. (syn. Yucca nana) | Harriman's yucca |

|

Yucca intermedia McKelvey | Intermediate yucca | |

|

Yucca jaliscensis (Trel.) Trel. | Izote | |

|

Yucca lacandonica Gómez Pompa & J.Valdés | Tropical yucca | |

|

Yucca linearifolia Clary | ||

|

|

Yucca luminosa (syn. Yucca rigida) | Blue yucca |

|

Yucca madrensis Gentry | Soco yucca | |

|

Yucca mixtecana García-Mend. | ||

| Yucca necopina Shinners | |||

|

Yucca neomexicana Wooton & Standl. | New Mexican Spanish bayonet | |

|

Yucca pallida McKelvey | Pale yucca | |

|

Yucca periculosa Baker | Izote | |

|

Yucca potosina Rzed. | ||

|

Yucca queretaroensis Piña Luján | ||

|

Yucca reverchonii Trel. | ||

|

|

Yucca rostrata Engelm. ex Trel. | Beaked yucca, Big Bend yucca |

|

Yucca rupicola Scheele | Texas yucca, or twist-leaf yucca | |

|

|

Yucca schidigera Roezl ex Ortgies | Mojave yucca |

|

Yucca × schottii | Hoary yucca or mountain yucca | |

|

Yucca sterilis (Neese & S.L.Welsh) S.L.Welsh & L.C.Higgins | ||

| Yucca tenuistyla Trel. | |||

|

|

Yucca thompsoniana Trel. | Thompson's yucca |

|

|

Yucca treculeana Carrière | Texas bayonet, Trecul's yucca |

|

|

Yucca utahensis McKelvey | |

|

Yucca valida Brandegee | Datilillo |

A number of other species previously classified in Yucca are now classified in the genera Dasylirion, Furcraea, Hesperaloe, Hesperoyucca, and Nolina.

Cultivars

From 1897 to 1907, Carl Ludwig Sprenger created and named 122 Yucca hybrids.

Gallery

-

Joshua trees (Yucca brevifolia), growing in the Mojave Desert

-

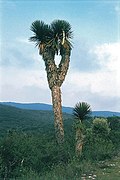

Unknown species near Orosí, Costa Rica

-

Yucca near Carlsbad Caverns National Park in New Mexico

-

Yucca harrimaniae also known as Harriman's yucca

-

Yucca faxoniana in Texas, with mature fruits

-

Yucca schidigera in Nevada, in full bloom

Notes

- ^ No species name is listed in state statutes, however the New Mexico Centennial Blue Book from 2012 references the soaptree yucca (Yucca elata) as one of the more widespread species in New Mexico.

References

- ^ "Yucca L." Germplasm Resources Information Network. United States Department of Agriculture. 2010-01-19. Archived from the original on 2010-05-30. Retrieved 2010-06-07.

- ^ Chase, M.W.; Reveal, J.L. & Fay, M.F. (2009), "A subfamilial classification for the expanded asparagalean families Amaryllidaceae, Asparagaceae, and Xanthorrhoeaceae", Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 161 (2): 132–136, doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.2009.00999.x

- ^ Irish, Gary (2000). Agaves, Yuccas, and Related Plants: a Gardener's Guide. Timber Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-88192-442-8.

- ^ Quattrocchi, Umberto (2000). CRC World Dictionary of Plant Names. Vol. 4 R-Z. Taylor & Francis US. p. 2862. ISBN 978-0-8493-2678-3.

- ^ ASALE, RAE-; RAE. "izote | Diccionario de la lengua española". «Diccionario de la lengua española» - Edición del Tricentenario (in Spanish). Retrieved 2021-11-23.

- ^ "Yucca gigantea Spineless yucca, Izote PFAF Plant Database". pfaf.org. Retrieved 2021-11-23.

- ^ Guillot Ortiz, Daniel (2009). El género Yucca L. en España. Piet van der Meer. Jaca: Jolube. p. 55. ISBN 978-84-937291-8-9. OCLC 1123383406.

- ^ Clary, K. H., & Simpson, B. B. (1995). Systematics and character evolution of the genus Yucca (Agavaceae): Evidence from morphology and molecular analyses. Botanical Sciences, (56), 77 - 88. https://doi.org/10.17129/botsci.1466

- ^ Segraves, Kari A.; Althoff, David M. & Pellmyr, Olle (1 October 2008). "The evolutionary ecology of cheating: does superficial oviposition facilitate the evolution of a cheater yucca moth?". Ecological Entomology. 33 (6): 765–770. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2311.2008.01031.x. S2CID 55871573.

- ^ Daniels, Jaret C. "Yucca Giant-Skipper Butterfly, Megathymus yuccae (Boisduval & Leconte) (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae)". Electronic Data Information Source. University of Florida IFAS Extension. Retrieved 2010-06-07.

- ^ "Ursine Giant-Skipper Megathymus ursus Poling, 1902". Butterflies and Moths of North America. Archived from the original on 2010-06-15. Retrieved 2010-06-07.

- ^ "Strecker's Giant-Skipper Megathymus streckeri (Skinner, 1895)". Butterflies and Moths of North America. Archived from the original on 2010-06-15. Retrieved 2010-06-07.

- ^ Couplan, François (1998). The Encyclopedia of Edible Plants of North America. McGraw Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-87983-821-8.

- ^ Baugh, Dick (1999). "the Miracle of Fire by Friction". In David Wescott (ed.). Primitive Technology: A Book of Earth Skills (10 ed.). pp. 32–33. ISBN 978-0-87905-911-8.

- ^

Buchanan, Rita (1 January 1999) [1987]. "Plant Fibers for Spinning and Stuffing". A Weaver's Garden: Growing Plants for Natural Dyes and Fibers. Mineola, New York: Courier Corporation. pp. 51–52. ISBN 9780486407128. Retrieved 26 September 2023.

Yucca leaves, and fibers derived from them, were some of the first plant materials used by early man in North America. Long before early hunters and gatherers settled down to building villages or raising crops, they already were making baskets, fishnets, carrying bags, sandals and mats from yucca and other native plant fibers. In the Southwest, yucca leaves are still used to make round trays and baskets. [...] During World War II, researchers studied the possibility of harvesting fibers from existing wild populations of yucca in the Southwest [...]. [...] Yucca fibers vary in length and fineness depending on the species, but in general they are softer and more flexible than sisal or agave fibers. [...] Hand-processed yucca fibers can be spun into fine yarns for use in weaving, braiding or twining.

- ^

United States Department of Agriculture (1880). "Vegetable Fibers". Report of the Commissioner of Agriculture for the year 1879. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 599. Retrieved 26 September 2023.

[...] specimens of yucca cordage and coarse 'cloth' (matting) from Y. filamentosa [...].

- ^ "Yucca: Health Benefits, Side Effects, Uses, Dose & Precautions". RxList. Retrieved 2023-01-28.

- ^ "FOAMATION". www.ingredion.com. Retrieved 2023-01-28.

- ^ Bononi, M., Guglielmi, G., Rocchi, P., & Tateo, F. (2013). First data on the antimicrobial activity of Yucca filamentosa L. bark extracts. Italian Journal of Food Science, 25(2), 238–238.

- ^ a b c Pieroni, Andrea (2005). Prance, Ghillean; Nesbitt, Mark (eds.). The Cultural History of Plants. Routledge. p. 33. ISBN 0415927463.

- ^ "Yucca: the November 2020 Houseplant of the Month". December 2020.

- ^ a b RHS A-Z encyclopedia of garden plants. United Kingdom: Dorling Kindersley. 2008. p. 1136. ISBN 978-1405332965.

- ^ "maquilishuat tree | plant | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2021-11-23.

- ^ World Checklist of Selected Plant Families, The Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, retrieved 2012-02-23, search for "Yucca"

- General

- Fritz Hochstätter (Hrsg.): Yucca (Agavaceae). Band 1 Dehiscent-fruited species in the Southwest and Midwest of the USA, Canada, and Baja California , Selbst Verlag, 2000. ISBN 3-00-005946-6

- Fritz Hochstätter (Hrsg.): Yucca (Agavaceae). Band 2 Indehiscent-fruited species in the Southwest, Midwest, and East of the USA, Selbst Verlag. 2002. ISBN 3-00-009008-8

- Fritz Hochstätter (Hrsg.): Yucca (Agavaceae). Band 3 Mexico , Selbst Verlag, 2004. ISBN 3-00-013124-8

External links

The dictionary definition of Yucca at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of Yucca at Wiktionary- Yucca species and their Common names - Fritz Hochstätter

- New Mexico Statutes and Court Rules: State Flower Archived 2013-10-22 at the Wayback Machine

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

Recent Comments